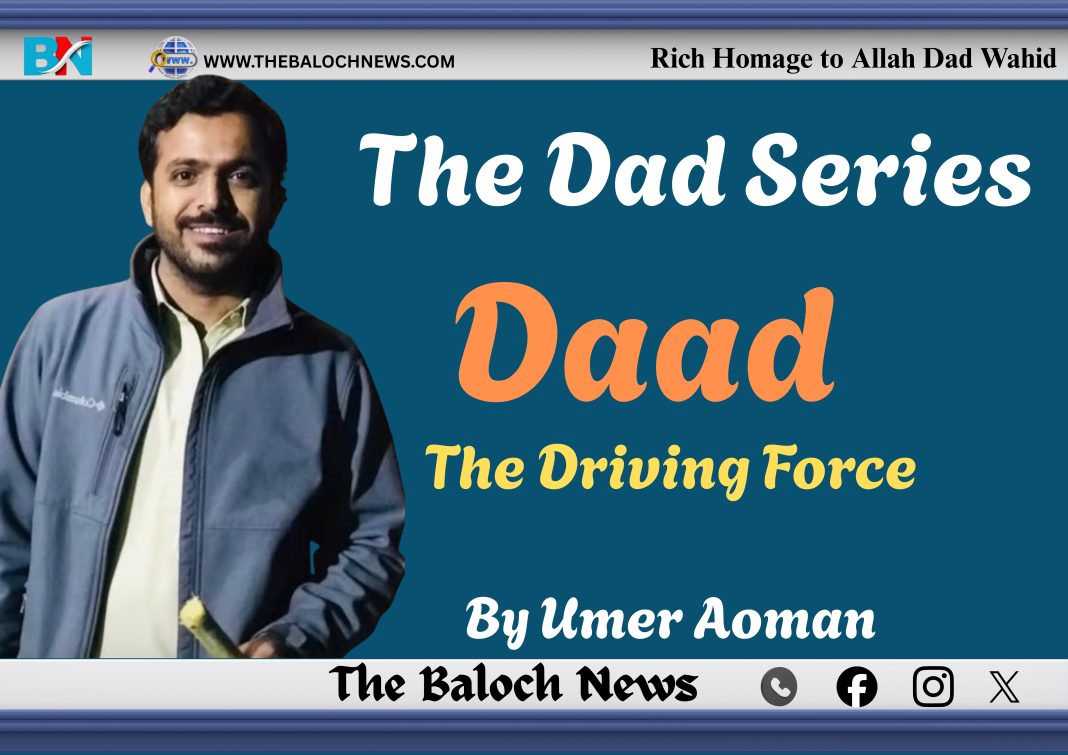

Some lives do not end with death; they disperse into memory, language, and unfinished conversations. Allah Dad Baloch was one such life. His presence ensured not through monuments or records alone, but through the ideas he cultivated, the words he defended, and the intellectual futures he imagined for others. In societies (particularly ours) where history is routinely erased, such endurance itself becomes a form of resistance.

On 4 February 2025, Allah Dad Baloch was taken from us in Turbat, Kech. His physical departure marked more than the loss of a young scholar and literary thinker; it signaled the silence of a voice deeply committed to language, literature, and critical inquiry. For those who knew him closely, his absence is not merely emotional—it is epistemic, a rupture in thought itself. The elimination of intellectuals has long been a strategy in regions where knowledge challenges power, and Balochistan is no exception.

I called him Daadul—a name born of affection and shared intellectual struggle. He was the reason my academic research did not remain confined to a university archive. My doctoral thesis, The Problems of Baloch Society through the Lens of One of the Prominent Contemporary Poetic Geniuses, Mubarak Qazi, became a book because Daadul insisted it must. At the time, I was living in Berlin, while he was in Turbat. Distance never diluted his resolve. Through persistent encouragement, he ensured the work reached completion.

That book (Qazism) exists, though it is not yet public, because he believed it should. In this sense, it belongs to him as much as it belongs to me. His insistence reflected a broader conviction: that knowledge must circulate, and that intellectual labor acquires meaning only when it enters public life—especially within marginalized societies where scholarship is often denied institutional support.

Daadul’s commitment to Balochi literature was neither sentimental nor nostalgic; it was rigorous and future-oriented. He understood language as a living archive of collective experience and a site of political struggle. He believed that languages survive not through preservation alone, but through translation—through the circulation of ideas across borders, histories, and intellectual traditions. Translation, for him, was not a secondary literary task but a primary ethical responsibility.

He envisioned bringing the most significant literary, philosophical, and historical works of the world into Balochi, convinced that Baloch society deserved direct and unmediated access to global thought. This vision challenged the structural marginalization of Baloch within Pakistan’s linguistic hierarchy, where dominant languages function as gatekeepers of knowledge. For Daadul, language was never ornamental. It was ethical, political, and necessary.

I first met him in Faqeer Colony, Karachi, when I went to escort him to the university. He had recently been admitted to the Department of History. Although it was our first encounter, it carried an immediate sense of familiarity. He spoke with striking clarity about world order, power struggles, and the politics of knowledge. He cited Noam Chomsky with ease and, in the same breath, invoked Mulla Fazul—placing him in conversation with figures such as Goethe and Sylvia Plath. He moved effortlessly between Balochi intellectual traditions and the global literary canon, refusing any hierarchy between them.

This intellectual fluidity was not performative; it reflected a deeply internalized belief that Balochi thought belonged within global conversations, not at their margins. Although I was his senior at the university, when Daadul spoke, I listened. I learned. He belonged to that rare category of students whose presence elevates intellectual space—whose questions unsettle certainty rather than seek approval.

Daadul was not a man of weapons. He was a man of words. Yet within a system sustained by silence and fear, words themselves are treated as threats. States have long feared intellectuals more than militants, because ideas endure. Among the Baloch, the bitter phrase Desi Farishta—coined by Sher Dil Gaib—refers to the Pakistani Army, the ISI, and death squads in Balochistan long documented by human rights groups as being associated with enforced disappearances, torture, and killings of Baloch students, poets, and thinkers. Allah Dad Baloch has now been added to this long and brutal history of intellectual erasure.

But…

Man wa Marga Cha Randh Hoún Nameeran Baan

Man Nazanán Mana TaoChe Paima Koshay

He lives in the book he compelled into existence.

He lives in the ideas he shared freely.

He lives in the future readers he believed would come.

To remember Allah Dad Baloch is not only to mourn his death; it is to recognize the systematic conditions that render such deaths possible. It is also to continue the work he valued—writing, translating, thinking, and refusing silence. In societies marked by repression, intellectual continuity becomes a moral obligation.

Some lives end quietly. Others transform into language.

Daadul became language.